Chile's looming right-wing shift

The past few years have been very good for the Latin American left. Since 2020 they’ve won presidential elections in Bolivia, Peru, Honduras, Chile, Colombia and Brazil. But recent developments in one of those countries could hold lessons for the decade to come.

At the beginning of 2022, the year seemed as if it would be the culmination of a clean progressive sweep in Chile. The country had just ushered in one of its most left-wing governments in recent memory, with a mandate for constitutional change backed by statement election victories and years of protests.

But as the year progressed, the unwieldy process of drafting the document, left-wing infighting, and sinking approval ratings for Boric all amounted to a debacle, and eventual fracaso, for progressives hoping to cement a new systemic framework to govern the country. The new constitution was rejected via referendum in September, by a margin of more than 20 points.

Now, as Boric’s approvals sink further into Pedro Castillo territory, the country is expected to yet again return to the polls in 2023 to elect a new constitutional convention. This time, however, the result is shaping up to be far different.

In a near mirror image of the last convention’s contours, one poll expects the next body to see the arrival of an outsized right. The survey, taken in December, shows 45% of the vote being shared between the Chile Vamos conservative bloc, far-right Republican Party and anti-establishment “Party of the People” respectively.

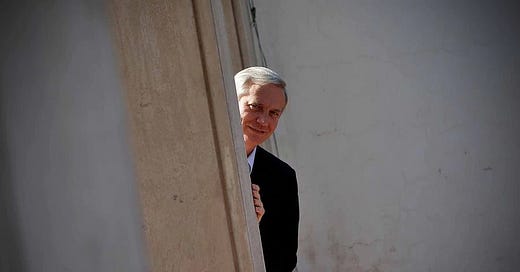

The Republicans, led by 2021’s runner-up presidential candidate José Antonio Kast, ran with the conservative bloc last time, but took a single percentage point. The aforementioned survey shows that this time around, they could ascend to 15%. A clear far-right constituency has emerged, though it must be pointed out that Chile’s conservative parties have always held nationalist and Pinochetist elements (Kast himself hails from UDI).

Meanwhile, the Party of the People is the personal vehicle of the last presidential election’s most perplexing candidate, businessman Franco Parisi. Though the party has claimed to be a big tent, Parisi ended up backing Kast in the second round of the presidential election. It can be assumed that the party would find closer friends in the Republicans than the left- some reports have even discussed a possible alliance.

Parties affiliated with the Boric government- the Communists, Broad Front and Social Democrats- only amount to 29% of the vote combined, a far cry from the near-majority the left commanded in 2021. The center-leftish Christian Democrats take another 5%, with the rest of the vote being rounded out by centrists, the center-right, or independents.

The next Chilean president won’t take office until 2026, but early presidential data tells a similar tale. In a recent poll from Research Chile, conservative UDI candidate Evelyn Matthei is the clear favorite, with nearly 34% of the vote. Kast’s second-place forecast of 21% alone brings the right’s total to over a majority, not even including lesser right-wing candidates, although Matthei is considered more of a moderate within her party.

None of this is set in stone. No one knows whether the polling will shift in the months between now and May's constitutional convention election (35% are still undecided), let alone a presidential vote to be held years from now. But the kind of approval hole that Boric currently finds himself in might be hard to shake off. Even after historic, energizing victories, the “backlash" or “revenge" effect tends to come into play quickly. This time around, it could really pack a punch.

Connections

Backlash elections are certainly real, but not a guarantee. In the US, we just saw an example of right-wing opposition overextending itself, and putting up a lackluster midterm performance as a result.

Approval ratings for left-affiliated leaders elsewhere in the region are a mixed bag. Lula is currently experiencing a honeymoon, while Fernández is far underwater. In Bolivia, Arce is in the negatives by single digits on average, while Pedro Castillo went completely off the rails and only dubiously held the leftist moniker anyway. Polls disagree on whether Petro’s honeymoon has wilted in Colombia, and in both Honduras and Mexico, incumbents still mostly hold over +20 approval.

Over in Europe, many leaders seem to have flailing approval at the moment. Boric, who has hit a wrenching 70% disapproval figure in polls, is by no means alone.